stop rebasing

Rebasing is in vogue. But if we don't stop to think before rewriting our history, it will just end up causing us pain in the future.

published 2020-11-16 by christopher cooper

okay, okay. Maybe the title is a bit strong. I’m describing a phenomenon in which people believe that your git history should always be a straight line, and that rebasing is always preferable to merging. That philosophy runs into problems really quickly. I’ve personally lost many hours of my time dealing with this in a project at a well-known company. How? Let’s start with the background.

First, why do people rebase instead of merging? If you don’t know what a rebase is, the Pro Git book provides a pretty good description. If you never rebase, merges can get pretty crazy. This is how a merge-only flow might work:

- You start working on a feature branch

- You make some commits

- There’s new commits on your main branch, so you merge it into your branch

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 a few times

- When completed, you merge the feature branch back into main1

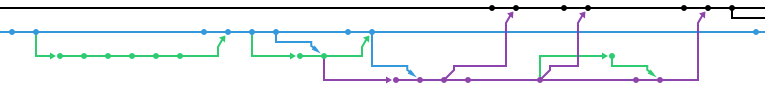

This results in a hard-to-decipher mess of merge commits, such as this example from my first major web development project. This history obscures the fact that your feature branch can usually be represented as simple diffs that can be applied cleanly onto main. Instead of this mess, rebasing lets us directly represent those diffs as clean commits on main, as if we never branched at all. This results in a nice, clean graph that shows the linear progression of new patches hitting main.

That seems good! And, in this most common case, it is. However, there seem to be a growing number of rebase fanatics that take this too far. They will always rebase instead of merging. Here’s why this can be a problem.

Rebasing violates append-only history. Generally speaking, git is based on the assumption that your commit history doesn’t change, except by appending new commits (including merge commits) to the end. Rewriting your history, aka rebasing, completely violates this assumption, and it needs a bunch of kludges to make it work. For example, pushing a rebased branch requires you to use --force-with-lease. (Don’t use --force!2)

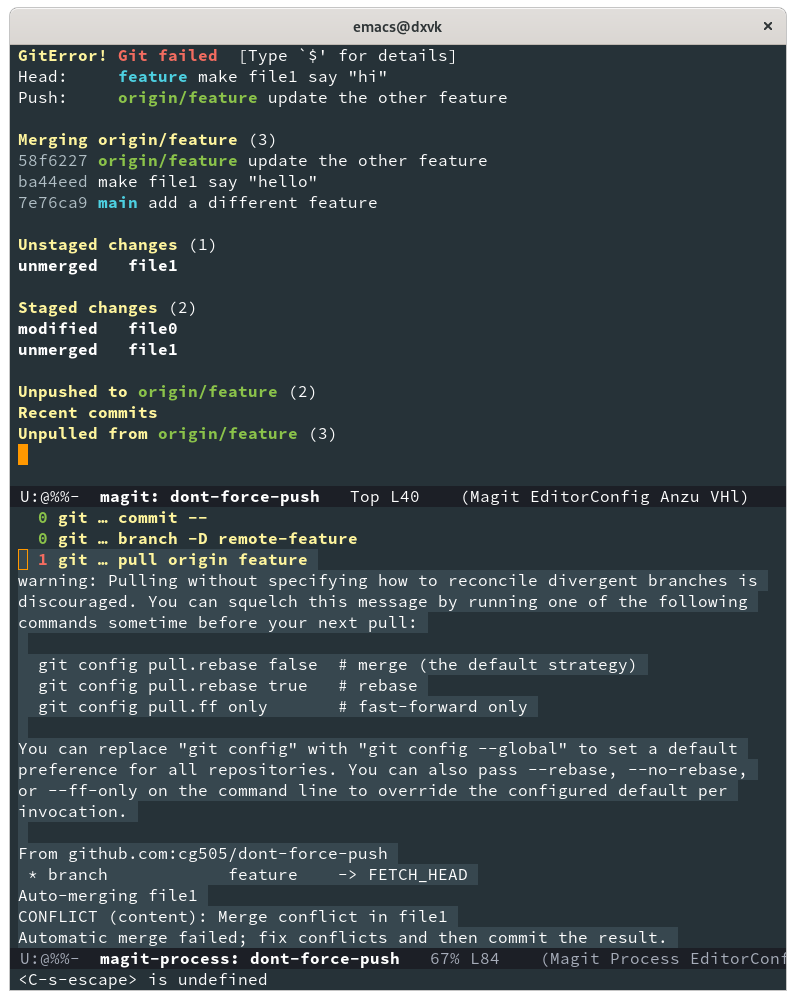

Because of this append-only assumption, it is disastrous to rebase a branch that someone else is also working on. You may be aware that you should never force push to main, but the rule is really “you should never force push a branch that another person has checked out”. This is because when the other person pulls this branch, git will attempt to reconcile the local (pre-force-push) branch history with the remote branch… creating a merge AND adding the old history back into the branch! The user now has to notice that this is an issue (hmm… why did git tell me it’s creating a merge commit?) and know how to manually resolve it (okay, the branch must have been force-pushed, gotta run git reset --hard origin/branch). If the other person has local changes, they have to determine how to cherry-pick those changes onto the new history. This is a nightmare, even when you’re super experienced with git. No one should have to do it, ever!

This example would not have caused any problems if my imaginary teammate had merged instead of rebased.

The reason this gets messy so fast is quite simple: in order to merge diverging histories, git compares to the most recent shared history. By rebasing, you are removing that shared history. In extremely very simple cases, git can recognize the “same” history in a rebased branch, but this detection breaks down as soon as any potential conflict arises.

The logical conclusion is that when you rebase and force-push, you must be confident that NOBODY ELSE has checked out the branch that you’re rebasing. You must never rebase and force-push your main branch. Rebasing is a very powerful tool that you should use, but ONLY on your own branches, ideally before they’re ever been pushed.

You may be thinking: “Why would anyone force-push a shared branch? Isn’t this a case of disproportionate outrage over a tiny issue?” People get in the mindset of “rebase, never merge”, and it is really easy for this to happen. I was on a team that was about 100 commits into a fork of an open source project, when there were some upstream changes that we wanted to pull in. I went ahead and set up the merge, resolved the conflicts, and opened a PR. However, the tech lead told me that they preferred to rebase everything in our fork on top of the upstream master. You should be able to identify this as a violation of the “don’t force-push shared branches” rule. It meant that every active feature branch had to be rebased on top of the new fork, which caused dozens of conflicts each time. What did we have to show for it? A cleaner commit graph. Not worth it.

— cg505

-

I use main to refer to your primary development branch, whether you call it

main,develop,master, or whatever else. ↩ -

Using

--forcecan accidentally overwrite git history that you didn’t expect to be there.--force-with-leaseis preferred because it checks that you know about the history that you are overwriting. ↩